The immune system in a healthy animal is constantly searching for potential threats. If the immune system identifies a disease threatening the animal, it produces antibodies that seek out the disease and mark it for destruction. The animal is protected and the immune system saves a “memory” of the disease so it can respond faster and more efficiently the next time it sees this same disease.

Vaccines are essentially a way to trick the immune system into launching a response against a disease even though the disease is not present. The immune system cannot tell the difference between a disease and its vaccine, so it produces antibodies and saves a memory of the disease just the same as if it was presented with the actual disease.

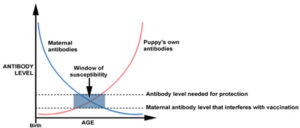

Assuming that the puppies’ mother is a healthy individual with a normal immune system, her body contains antibodies against all the diseases she’s experienced, regardless of whether that’s via exposure or via vaccination. When puppies are first born, their immune system has not finished developing and therefore they have absolutely NO protection against disease, including often fatal diseases such as parvovirus and distemper.

To provide temporary protection to her puppies while their immune systems finish developing, the mother “gives” some of her antibodies to her puppies. She does this by producing colostrum, which is a special type of milk packed with antibodies. The puppies drink the colostrum, and for a few months the mother’s antibodies circulate in the puppies’ bodies, protecting them against disease until the puppies’ immune systems are mature enough to take over the responsibility.

As mentioned above, antibodies cannot tell the difference between a disease and a vaccine. Therefore, if a puppy still has lots of antibodies from their mother and they get their first puppy vaccine, the mother’s antibodies will block the vaccine, thinking that it is the disease. The puppy’s immune system cannot launch its own response to the vaccine because it never “sees” the vaccine.

Antibodies have a natural break-down process, and eventually the amount of maternal antibodies has declined to the extent that it can no longer protect the puppy from disease. This also means it will no longer block vaccines. Ideally, this coincides with the puppy’s own immune system becoming mature enough to take over responsibility for protecting the puppy. At that point, we can vaccinate a puppy and the puppy’s immune system will respond, producing both antibodies and a memory of the disease

The amount of maternal antibodies transferred is not the same in every puppy. There are tons of factors that go into this – the mother’s own immune system, how much colostrum the puppy received, the diseases present in the environment, etc. However, the RATE at which maternal antibodies break down is consistent. Based on averages, protection provided by maternal antibodies is usually gone by 14-16 weeks of age. But, of course, your puppy is not an average. In some cases maternal protection might be gone by 6 weeks, in others it might be gone at 14 weeks. This causes a conundrum. We could wait to start the vaccines until 16 weeks, when we’re pretty confident maternal antibody protection is gone, but if that individual puppy’s maternal antibody protection was gone by 6 weeks, the puppy would be left unprotected for weeks before being vaccinated.

The solution is the reason we give a series of vaccines. We start vaccinating puppies at 6-8 weeks, which is typically when the puppy’s immune system has the potential to respond to a vaccine, and continue boostering the vaccine every 2-4 weeks until at least 16 weeks. By doing this, we are likely to vaccinate the puppy as soon as the protection from maternal antibodies has declined enough that it is no longer protecting the puppy (and blocking the vaccine), thereby maintaining the puppy’s protection.

Source: https://thevillageveterinaryhospital.com/medicalsurgical-info/

Although the amount of maternal antibodies transferred to the puppies is not the same, the RATE at which it breaks down is consistent. Therefore, if we know the amount a puppy starts with, we can calculate the time point at which enough maternal antibodies will be gone for a puppy’s immune system to respond to a vaccine. This test is called a nomograph. More information on nomographs can be found here.

This information probably isn’t necessary in most cases, but it does provide useful and interesting information about the puppy’s immune protection. I believe this is most helpful in planning a puppy’s socialization. If you know how protected or at-risk a puppy is at a particular time, you can adjust their socialization schedule accordingly. In the absence of this information, puppy parents should exercise excellent biosecurity techniques and assume their puppy is at risk of contracting disease until their vaccine schedule is complete.

In summary, these are the two vaccine protocols which are valid and appropriate for puppies. These vaccine protocols take into consideration the physiology of the early immune system and provide protection against deadly diseases at the earliest possible opportunity.

1) Start core vaccine series at 6-8 weeks and continue every 2-4 weeks until 16 weeks of age or greater

2) Consult with your veterinarian to obtain a nomograph and vaccinate according to the results

I hope this information has been helpful and has helped to explain the science behind puppy vaccines. Here’s to less stress and more healthy puppies!

2 Comments

Kathryn Jones · November 27, 2019 at 12:25 pm

This is an excellent explanation! May I share?

Dr. Kristina Baltutis · November 27, 2019 at 3:39 pm

Of course!